Queens Medical Professional

Association (QMPA)

Abstract

Queens Medical Professional Association is seeking a grant to fund our

new CARE Program. The program aims to increase integration of Electronic

Health Records (EHR) into the primary care medical practices in order to roll

out an experimental new payment model. The new flexible payment models in

turn are expected to increase health care access in the medically underserved

areas of Queens. QMPA’s first objective is to implement a new payment model

by the end of the first year after studying the intricate details of each

practice and developing new well-tuned workflows. The second year will be

focused on the evaluation of 10 core assessments to aid in determining the

success of the program. QMPA request for $834,249 in order to form the new

program and train other medical professionals from the primary care sites

throughout Queens.

Table of Contents

Statement of Need 3

1.1 QMPA Core Assessment Review Evaluation Project 3

1.2 The Alternative Payment Models and Value Based Payment 7

Year 1: Understanding the Organization of Private Practices 12

Year 2: New Payment Models and Evaluation Changes 17

Organizational Capacity 18

2.1 Organization and Administration 18

Finance Branch 19

Healthcare Section 20

Social Provisions Division 20

2.2 Operational Plan 20

2.3 Organization Structure and Staffing 21

Funding and Sustainability 22

3.1 Budget Narrative 22

3.2 Model Sustainability 25

Evaluation 25

Supporting Documents 27

Appendix 1 – Placement of the CARE Program within QMPA 27

Appendix 2 – CARE Program 27

Appendix 3 – Overall Total Project Budget for Electronic

Healthcare Initiative 28

Statement of Need

1.1 QMPA Core Assessment Review Evaluation Project

The Queens Medical Professional

Association plans to initiate its CARE program with three main objectives:

1. Clinical

Care Team Transformation

2. Clinical

Electronic Integration

3. Financial

Planning, Implementation, and Control

Clinical care team transformations

will require a push by healthcare professionals to learn the ins and outs of

the software. To aid them are our frontline project managers and technology

specialists. After the initial observation of each medical practice, the main

office of the organization will host a weekly workshop to address ongoing EHR

issues and possible improvements from suggestions surveyed. Project managers

will have to actively take part in the learning process to make sure that the

healthcare professionals do not feel overburdened by the process.

Clinical electronic integration is

the crux of heavily integrating practices with new electronic health records

(EHRs). Integration means that the EHRs are utilized at a greater level than

just a record-keeping device. It means that the records are actively being

used during collaboration with other healthcare professionals for wide

reaching projects and quality improvement measures. Other aspects of EHRs are

to enable the health care provider to gain access to the patient’s full

medical history through hospital, group practice and private company data.

Financial planning,

implementation, and control will be the main emphasis for the second phase of

the program when it switches from quality measures and EHR improvements to

payment model adaptation. Their needs to be a strict accounting system in

place to calculate the potential revenue, loss money from denied claims, cash

flow from cost sharing measures (such as copay and coinsurance), and other

possible expenses. The new model must be shown not only as making more

revenue, but also being efficient. An increase in revenue will mean little if

the staff is constantly working overtime. Gains in revenue can be reallocated

towards improving patient quality of care.

Technology, while infinite in its

potential, continues to struggle in its adaption to various human complex

adaptive systems. In 2009, Health Information Technology for Economic and

Clinical Health (HITECH) Act earmarked nearly $30 billion towards electronic

health record adoption and meaningful use (Rosenbaum, 2015). However, despite

massive government incentive towards the implementation of electronic health

records, hospitals and private practices have struggled to fully integrate

technology into the healthcare setting. The year 2012 brought a substantial

increase in EHR participation in both the hospital and professional practice

setting with 63.8% of eligible hospitals participating and 48.0% of eligible

professionals participating (US Government Accountability Office, 2014). Since

then there has been a trend of increasing physician participation in

electronic health records. Unfortunately, despite the increased participation,

many of the EHRs have been used for syndrome surveillance, laboratory

reporting, and registries instead of public health efforts (Friedman, Parrish

& Ross, 2013).

Another issue, is closely tied to

EHRs is reimbursement. The traditional payment model was the fee-for-service

reimbursement where cost of treatment was tied to type of service provided.

Unfortunately, this payment model incentivizes medical professionals to

overprovide healthcare services (Porter, 2012). Valued based reimbursement

instead attempts to focus on patient metrics to determine reimbursement. This

is not the only alternative reimbursement plan available. Other alternatives

that have been tested are capitation payments and bundle payments. Capitation

payments are regular lump sum payments given to the provider regardless of

number of services utilized. The

integration of EHRs enables the tracking of metrics, which makes value based

reimbursement possible.

The combination of healthcare and

technology contains massive untapped potential. The ability to coordinate

public health programs with physicians dispersed throughout a region on

massive scale with immediate adequate health feedback opens the field to

tele-health. Not only would the public health officials be able to perform

epidemiology on a massive scale, but patients would also be able to access

their health records when needed. In addition, the interconnection of the

health records with major medical institutions would enable treatments with

thorough patient history provided by the primary care provider. However,

implementation hiccups have stalled these visions of technology integration. The

Queens Medical Professional Association aims to aid medical providers in

gradually implementing changes over time to create a smooth transition towards

efficient EHR integration into the private practice workflow. The purpose of

the project is to lay the groundwork for possible later implementations of a

new payment model.

Queens Medical Professionals

Association (QMPA) intends to confront the fee-for-service model still present

in the primary care practices of Queens to improve healthcare access and

streamline primary care practices. According the US Government census, the

borough of Queens in New York City has a population of 2,333,054 residents.

Within this group reside some 5,049 physicians. Of the total number of

physicians, 1,897 are primary care providers (Robert Graham Center, 2015).[1]

Queens has lower physician to population ratio than New York State overall

with certain areas such as Corona, Jamaica, and Astoria designated as

medically underserved areas. This ratio indicates the strain placed on the

present primary care physicians attempting to maintain the health of their

respective neighborhoods. What medical care is available is often swamped with

numerous patients. Doctors within the neighborhood of Flushing and Elmhurst

have reached patient loads of over 2,000 per primary care provider.[2]

Doctors are not required to accept large patients loads, however, they do so

in order to maintain their revenue stream as insurers have paid less for

“nonessential” services. Predictably, the large patient loads result in

shorter face-to-face interactions with the doctor ranging from a maximum of

one hour to a minimum of 15 minutes. A doctor with an average of 30 patients

daily would require at least 15 hours to provide quality healthcare, difficult

to achieve even in the best of conditions.[3]

Heavy time burdens as well as lack of incentives discourage physicians from

coordinating patient care with other healthcare professionals. The end result

is an endless array of paperwork back and forth with other health

institutions, over issues patient issues that may have been already covered a

month ago.

QMPA’s efforts will be directed

towards the neighborhood of Corona. Corona presents a perfect preliminary

testing ground for a transition to value-based healthcare. Like most of

America, its population suffers from rising chronic health issues such as a

25% obesity rate and a 14% diabetes rate. 66% of the population is foreign born

and 53% of neighborhood has limited English proficiency (NYC DOHMH, 2015). The

cultures from this neighborhood vary widely and will significantly affect

patient relations with medical professionals. Overcoming these challenges will

demonstrate that the program is scalable to the rest of Queens.

While there have been government

incentive programs towards the implementation of EHR systems at private

practices such as HITECH, they often lack detailed instruction on how to

effectively use EHRs within the medical workflow. Other programs such as PCMH

focus only on the specific on aspects of the EHR such as registry reports.

Building on the past experiences of IT specialists, group health insurance,

value reimbursement programs, and government efforts, this programs seeks to

solidify the connection between EHR and primary care.

1.2 The Alternative Payment Models and Value Based

Payment

A total of 30 clinics have agreed

to participate in the CARE program. They are scattered throughout the Queens

area stretching from Astoria to Jamaica. While project is mainly focused on

the neighborhood of Corona with its 10 medical clinics, other practices

throughout Queens are also involved to see if the program is flexible in

different environments.

At the center of the program are

ten core assessments of quality healthcare:

1. Cholesterol

management

2. Cancer

management

3. Hypertension

treatment

4. Diabetes

management

5. Obesity

management

6. Mental

health Guidance

7. Gastro-intestinal

health (report on bowel movements, treatment plans)

8. Smoking

(treatment for addiction, long term plan)

9. Drinking

(report for liver function, treatment for addiction, long term plan)

10. Healthcare

cooperation (P2P referrals, online portals, shared patient access)

These ten objectives are to be

promoted at 30 primary care practices and are the core focus of the basic

reports.

Cholesterol management

concentrates on the results of lipid panel blood tests. The usual range of

cholesterol is less than 200mg/dL (Laberge, 2013). Often patients with an

overconsumption of fat in diet, a lack of exercise, or a genetic disorder

suffers from hyperlipidemia and other related cholesterol diseases. The levels

of cholesterol are generally asymptomatic in that they do not directly cause

diseases. Rather they serve as cofactors to other issues such as emboli and

thrombi development. The favored medications for treatment of

hypercholesterolemia (aka hyperlipidemia) are statins. Monitoring the total

cholesterol levels and medication schedule will enable for the development of

future long-term plans.

Cancer management is focused on

detecting the cancers when they are in the early stages of 0 and I. Early

treatment prevents the cancer from metastasizing and developing into stages II

– IV. The management of cancer will be difficult considering that there are so

many different types of cancers possible for various organs throughout the

body. A pap smear is used to determine cervical cancer. A mammogram is used to

determine breast cancer. CBC blood tests can be used to determine cancer of

different types of blood cells. What will be vital to the process is recording

the initial diagnosis/discovery and connecting it to the prognosis and overall

outcome. Steps must be taken to connect the electronic health records of the

primary care and of the oncologist. This integration will help for better

treatment or prevention of cancer relapse.

The medical community recently has

switched to new hypertension guidelines following the 140/90 to

130/80-baseline change. These new guidelines are expected to help in

preventative healthcare as treatment of hypertension early will help prevent

the rise of later chronic correlated diseases. However, even the experts are

still debating about the controversial guideline changes (Bakris, 2018). Some

common medications used for treatment of hypertension are diuretics,

beta-blockers, and ACE inhibitors. Analyzing the progress of medication

overtime will help determine if treatment is effective.

Diabetes measures will be based

off HbA1c levels as well as current glucose levels. The HbA1c test will be

used to determine whether or not the patient has diabetes, pre-diabetes, or no

diabetes. Treatment will also vary depending on the severity of the disease. Depending

on the medical practitioner’s decision, patients will be given a specific type

of medication such as metformin. The medication consumption and overall

schedule will be recorded on the EHR. For patients already with the diagnosis

of diabetes, the glucose levels will be monitored through the finger prick

tests. Glucose levels over time will be observed through integrated blood

testing machines.

Obesity diagnosis are closely

linked to the patient’s body mass index (BMI). The acceptable BMI range varies

depending on the gender and age. For adults the commonly held parameters are

that a BMI under 18.5 is considered underweight while a BMI of 30 or more is

considered obese (McPherson, 2008). For children and adolescents BMI

percentiles are used for an overall comparison with the rest of the

population. The gathering of BMI data will be simple considering the

collection of weight and height during almost every physician office visit. The

important factor will be to look out for possible comorbidity with other

diseases such as diabetes or coronary artery disease.

Mental health has long puzzled

primary health care practitioners. Often little resources or follow up are

provided by primary care physicians. Most mentally ill patients are referred

to a psychiatrist or other mental health services with little to no integration

between the services. The stigma of mental illness persists to this day,

however, primary care practices have a duty to perform a first level of care. One

of the most common mental illnesses is depression. Physicians should look

carefully into the patient’s behavior for possible signs of depression and

complete the assessment with PH-2 and PH-9 questionnaires. There is a strong

emphasis on collaborating with other mental health services to make sure that

the patient is attended to early to prevent exacerbating the situation later

on.

Digestive tract health is of

especial vital importance for the elderly and those with other comorbid gastrointestinal

diseases. Poor bowel movements, difficulty excreting stool, and bowel

incontinence heavily affect one’s quality of life and can exacerbate other

health conditions. For this reason close integration with the gastrointestinal

specialist is needed to make sure patients received a full consultation and if

needed, an endoscopy.

Smoking and drinking are

considered lifestyle decisions that can negatively impact your health. The

correlation between smoking and lung disease is strong, but not guaranteed.

The same issue can be seen with the consumption of alcoholic beverages and its

connection to liver disease. For the primary care physician, these guilty

pleasures will be difficult to wean patients off of. The primary determination

needed before starting smoking cessation and or alcohol counseling will be the

patient’s decision. If and only if the patient fully participates in the

program will full resources be utilized.

Healthcare cooperation is a factor

that will be based off multiple different measures. One of the easiest ways to

measure healthcare integration is to record the sharing of patient charts and

the utilization of e-referrals. Other more difficult aspects are the meetings

between healthcare workers regarding a specific patient’s needs. These will

have to be recorded through fax, email, or logging if done through telecoms.

The program is broken into two

parts:

1. Year

1: Understanding the Organization of Private Practices

2. Year

2: Evaluation Changes and New Payment Models

Year 1: Understanding the Organization of Private

Practices

While the general structure of a

primary care office remains unchanged, each practice has its own work

organization and workflow. A specific study must be undertaken to determine

the weaknesses and the strengths of each practice. Within the first month a

project manager should have visited and observed their 10 assigned medical

practices at least three times. Each project manager should have acquired the

5 W’s of each practice. Who are the employees (details on the staff)? What are

the procedures and policies of the practice? Where is the practice established

and from where does majority of its patients hail from? When is the practice

open? How does the practice’s policies and time organization affect the overall

practice and its interaction with patients? Besides these basic five points,

the project managers are free to choose what they considered vital to the

report.

On the last day of the first month

of the initiative, the program managers will submit a preliminary report on

the status and condition of their 10 assigned medical practices. Then, a

meeting will be held involving all members of the project to discuss potential

hazards for each clinic. Focus will be placed on the top three expected

difficult medical practices with the ultimate goal of working out any kinks

before implementation of continuous quality improvement (CQI).

A tally will also be made to determine which

are the five top EHRs among the 30 medical practices. The EHR specialist and

IT assistant will focus their efforts on the EHR priority list. However, the

IT assistant will focus more on the well known EHRs that have more product

support, while the EHR specialists centers their attention on the more obscure

EHRs.

On the second month, the project

manager will write a similar basic report with greater emphasis on small

nuances of each employee at the practice. However, this time the project

manager will extract patient data from the practice’s EHR to determine out of

the entire patient population, which patients require follow up services or

treatment for the core measures listed above. Separate lists of patients will

be generated for each core assessment.[4] Once

the list for each core assessment is complete, the project manager will

compile a separate report with the data. The report will describe the

practices’ overall first stage of patient treatment percentage and follow up

treatment percentage on each of the core assessments. A review of the report

will allow us to determine, which of the ten sectors the physician is lacking

in. Project managers can identify areas needing improvement and can focus

their efforts on cooperating with practices to increase patient data

transparency.

Core assessment number 10 will use a different formula for

the report.

The expected score of a first time

pass without any changes in policy will be a lenient cut off of 50%. The

expectation is that the score will rise overtime as some improvements have

been made.

The results of the report must be

discussed with physicians, allied health staff, and administrative workers to

determine if there is an error with EHR data compilation. Sometimes healthcare

practices forget an extra click or neglect to use structured data resulting in

skewed results when using the registry. A randomized 10% of patient records

from each practice will be pulled from the patient groups with one of the nine

health-related conditions as well as 10% from the patient group without the

conditions. The randomly selected groups will be analyzed for health history

and to determine if the necessary conditions exist or that the patient’s

health falls into the parameters of listed health condition. Only after this

preliminary check is completed can suggestions of changes can be done.

With both reports in hand, the

project managers will have another meeting, this time with the president and

executive assistant. The group will go over the possible suggestions and improvements.

Suggestions for improvements have three tiers:

Low tier suggestions are EHR

methodology changes. QMPA provides EHR training for reporting and data

management as well as consultation regarding system integration of new payment

models. Often physicians and associated medical staff are not familiar with

the updates and expanded capabilities of their EHR software. All too often

only the base requirements of the program such as appointment scheduling and

SOAP note writing are utilized. Project managers up to date on the latest EHR

software will be able to point out how new chains of commands can streamline a

billing process or how template usage can be adapted for patients.

Middle tier suggestions are to

allied health or physicians. Perhaps the physician has been using one test as

a core part of his assessment when there would be other more effective tests.

Or perhaps allied health staff was unaware of recent research findings on a

specific procedure. Recent research findings can be integrated into practices’

for a more efficient method of introducing treatment change.

Top tier suggestions are

policy-based changes that will dramatically affect the practice’s workflow and

patient interactions. Hiring auxiliary staff to handle insurance and other

medical paperwork in conjunction with using other health practitioners is a

few of such examples. The considerable change to the structure of the practice

will require group huddles and concentrated dedication to the new model system

developed.

On the third month, project

managers will implement the suggestions and turn theory into practice. Working

with medical professionals, project managers will coordinate the various

suggestions worked out at the meeting. At the same time, QMPA will start to

host weekly workshops regarding EHRs as well as meetings for improved workflow

designs. The weekly workshops will be held on a weekday or weekend depending

on medical professional availability. Each workshop will feature three EHR

software programs and their order sequences for analyzing core health

assessments. Also will include specific troubleshooting questions and possible

efficiency improvements. Finalized workflow charts of each practice are

devised after the project manager believes he or she has sufficient

understanding of the practice’s ins and outs. Evaluation of the suggestions

occurs after three months or a quarterly. After a cycle of suggestion/improvements

and evaluations, the end of the first year will bring the significant top tier

improvement, a new payment model.

Year 2: New Payment Models and Evaluation Changes

Research from the prior year is

used to determine the suitable alternate payment options to offer to different

medical practices. For practices looking to maintain independent from hospital

affiliations and group practice networks, retainer-based practice, with its

direct payment model from patient to physician. For practices with a large

share of Medicaid and Medicare patient, shared savings programs would be more

suited. For practices that see patients with insurance from large employers

such as government agencies, Accountable Care Organizations might be the way

to go. Regardless, most these major changes to the payment model are not

expected to result in major financial hardship for practices (Friedberg, Chen,

White, Jung, Raaen, Hirshman, & Lipinski (2015). The start of the New Year

will be an optimal time to introduce a new payment model, as both the medical

professionals and the patient will have their spirits buoyed by the

festivities. The next four quarterlies will be centered on evaluations of the

new payment model and the continuing quality of the 10 core assessments.

Changing payment models is

expected to cause a considerable amount of confusion for older primary care

physicians with less developed systems. Greater effort in terms of

consultation and training will be provided to these practices. Another issue

bound to turn up is the lack of patient healthcare progress. Unless there is

significant social, economic incentive and or willpower, many patients will

struggle to break old habits and routines. For these issues, referrals to

specialists, counselors and or patient management companies are recommended.

The third problem is that Electronic Health Records(EHR) software is not

standardize and the different software will make coordinating efforts

difficult. Our trainers will take a survey of EHRs being used by the 30

primary care providers. After compiling a list of EHRs, our trainers will

contact the EHR companies for software demonstrations.

Organizational Capacity

2.1 Organization and Administration

Queens Medical Professional

Association has a ten-year history of aiding medical professionals. It all

started ten years ago on December 2008 with the US markets collapsing under

the weight of the subprime mortgage crisis. Doctor Omnes Amigon and his group

of medical friends came together to discuss the inevitable increase in

patients without insurance. In addition, with the new president’s pledge to

reform healthcare there was a storm brewing for healthcare industry that was

bound to upset the current standard. With their practices in Astoria, Jackson

Heights, and Corona, the doctors decided that they needed to band together to

provide health services to the community in this time of great need. At the

same time, this new group of medical professionals would provide a vital networking

tool to discuss daily issues encountered at their practices and ways to

improve them. They formed the Queens Medical Professional Association with the

first goal of setting up a community health fair.

The first community health fair

was held on August 2019 at the Dutch Kills Playground in Astoria with

cooperation from the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, Department of

Parks and Recreation, and local church groups. Since then, the organization

has held the annual community health fair at different parks throughout

Astoria, Jackson Heights, Corona, Elmhurst, and Woodside. At the health fair

doctors provide blood pressure readings, glucose readings, basic vitals check,

and health consultations. Each participant in the health fair was provided a basic

health folder packed with preventative health education and their subjective,

objective, assessment, plan (SOAP) note of the day. At the end before leaving

the health fair, a volunteer takes the carbon copy of the patient’s SOAP note

and keeps it on file. During the next weekend, the doctors will pick out

particular worrying cases to follow up on.

Collaborations with community

organizations were vital to our organization’s initial success in providing

care to many patients. About 36% of the population of Corona and Elmhurst do

not have any form of health insurance (King, Hinterland, Dragan, Driver,

Harris, Gwynn, & Bassett, 2015). Thus, it was more likely for these

individuals during crises of health to go to the local hospital or community health

centers.

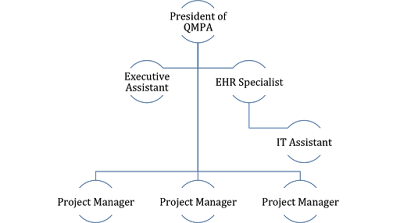

The structure of QMPA is based on

the hierarchical model of organization. The founder, Doctor Amigon, is the

association’s president. Under him are three basic sections of the

organization: Finance Branch, Healthcare Section, and Social Provision

Division.[5] The

newly proposed CARE program would be placed under the healthcare section.

Finance Branch

John Chen CPA, has run the finance

department since its original creation in 2008. He is a close friend of Dr.

Amigon and aids in sorting out the association’s finances. Helping him is our

resident, retired bookkeeper, Sally Hu. Sally was originally a patient of Mr.

Amigon and leapt and the chance to participate in community affairs.

Throughout the years they have been aided by accounting interns brought over

from the CUNY Colleges. Both, Sally and John have done a fantastic job at

organizing the money pooled at events for future events. They have also help

the organization keep track of expenses and provided reports for expected

future expenses.

Healthcare Section

The health section is blessed with

Dr. Amigon’s close friends from medical school. It comprises of a group of 12

doctors all in primary care. Over time the group has expanded to include

specialists and other allied health professionals such as medical assistants.

Social Provisions Division

The social section is composed of

church and other religious leaders as well as nongovernment organizations from

the neighborhoods. Old friends Sammy Lopez and Daisy Lopez, restaurant

storeowners from Corona, lead the social section in community discussions at

parks, hospices, church, bingo halls, and town hall meetings. Both have just

recently retired from the food industry and have poured their soul into

community efforts.

2.2 Operational Plan

Out CARE program will be working

alongside religious organizations from the Eternal Love Baptist Church, NY

Dong Yang First Church, St. Paul The Apostle Church, Queens Church of Christ,

and the Latin American Pentecostal Church. The first and second year

objectives also coincide with NYC government community health efforts within

the neighborhood.

2.3 Organization Structure and Staffing

For our program we have formed a

specific team of seven people for the task.[6]

At the top is President Amigon who directs the general basis of the program.

He oversees the organization’s funding and human networking connections. He is

aided by an executive assistant to deal with a variety of matters ranging from

phone calls to presentation setups. An IT subgroup of two people: EHR

specialist and IT Assistant are in charge of computer related issues. The EHR

specialists will be acquainted with popular EHR software such as Epic, MDLand, eClinicalworks and

allscripts. By being familiar with

the programs, the EHR specialist should also know the possible ways to change

the programming chain. This changing point is where the IT assistant comes in.

The IT assistant will provide computer troubleshooting for the transition

process and during computer system updates. The core of the initiative lies

with the three project managers who will oversee the entire process from start

to finish at the 30 medical practices. They will travel for face-to-face

interactions with the doctors they are assigned to.

Table 1: Roles and Responsibilities

of CARE Program

|

Role

|

Responsibilities

|

|

President

|

Directing program, networking with other execs, General

guidance

|

|

Executive Assistant

|

Administrative tasks: Answering phone, setting

appointments, organizing files in numerical order, writing up meeting

minutes

|

|

EHR Specialist

|

EHR functionality, Software adaption, troubleshooting

|

|

IT Assistant

|

Software clearance, troubleshooting

|

|

Project Manager

|

Physical travel to practices, assessment of practices,

reports, communication skills

|

Funding and Sustainability

3.1 Budget Narrative

QMPA has estimated the cost of the

two-year value based health care program to be $834,240. This cost is gathered

from annual salary, fringe benefits and organizational expenses and

multiplying that total, $417,120 by two to get $834,240. A further breakdown

of the individual portions of the total annual cost is available below.

|

Type

of Expense

|

Cost

|

|

Personnel

|

$375,204.00

|

|

Other Than Personnel Expense

|

$41,916.00

|

|

$417,120.00

|

|

|

Two year cost expense

|

$834,240.00

|

Table 2: Annual

QMPA Expenses

The president’s salary is not

included on this list as the organization already provides him with

significant perks and benefits. The executive assistant is given $37,440. The

EHR specialist is given $54,600 for their technical computer software

expertise. Their skills and knowledge will be actively applied to maintain the

program schedule. The IT assistant has a low salary of $31,200. The hope is to

hire a student graduate of computer science searching for experience for later

career advancement. Each project manager has a salary of $49,400 each for a

total of $148,200 for the three of them. Since they will perform the brunt of

the on the ground activities, they will be granted the most leeway in terms of

flexible time schedules. Additional project managers may be sought if the

patient care workload and time constraints prove to be too taxing.

|

Title

|

#

|

Hourly

|

Hours

|

FTE

|

Weekly Salary

|

Annual Salary

|

Annual Cost

|

|

President

|

1

|

$-

|

-

|

0.00

|

$-

|

$-

|

$-

|

|

Administrative

Assistant

|

1

|

$18.00

|

40.00

|

1.00

|

$720.00

|

$37,440.00

|

$37,440.00

|

|

EHR

Specialist

|

1

|

$21.00

|

50.00

|

1.25

|

$1,050.00

|

$54,600.00

|

$54,600.00

|

|

IT

Assistant

|

1

|

$15.00

|

40.00

|

1.00

|

$600.00

|

$31,200.00

|

$31,200.00

|

|

Project

Manager

|

3

|

$19.00

|

50.00

|

1.25

|

$950.00

|

$49,400.00

|

$148,200.00

|

|

|

7

|

$73.00

|

180.00

|

|

$3,320.00

|

$172,640.00

|

$271,440.00

|

Table 3: Salary

Breakdown of Staff

Fringe benefits include a health

savings account, a free monthly metro card, and childcare that are 38% of the

original salary provided. The health savings account will be a portion of a

group health insurance program with a total annual cost of $42,000. Health

expenses from medication to copay will be considered a valid expenditure of an

employee’s health benefits. For transportation, each staff member receives a

monthly-unlimited MTA metro card at the price of $121 per person for a total

of $10,164. Substantial traffic as well as difficulties with parking has lead

to the use of the metro card instead of a shared organization car. A childcare

fund of $1,000 monthly is available for those with children under 21. The

childcare fund can be used for anything child related from babysitting to

healthy food. Both the health savings account and the childcare fund roll over

and do not expire.

|

Type

of Benefit

|

#

|

Monthly/Person

|

Annual Cost/Person

|

Cost to Organization

|

% Salary Cost

|

|

Health

Savings Account

|

7

|

$400.00

|

$4,800.00

|

$33,600.00

|

12.38%

|

|

Child

Care

|

5

|

$1,000.00

|

$12,000.00

|

$60,000.00

|

22.10%

|

|

Transportation

|

7

|

$121.00

|

$1,452.00

|

$10,164.00

|

3.74%

|

|

19

|

$1,521.00

|

$18,252.00

|

$103,764.00

|

38.23%

|

Table 4: Fringe

Benefits

The rent for the association’s

headquarters is provided at discount cost. The utilities, including water,

electricity, phone, and heat, are compounded together, also at discount cost,

for $60 a month. The meeting fees and travel expenses are allocated to long

distance travel to conferences and meetings with other professionals involved

with healthcare technology and organization. Training expenses will fund the

weekly workshops held at the association, while the consultation costs will be

contractual depending on the stage of the program. Insurance costs are geared

towards coverage of the activities held by the association. Food costs will be

geared towards catering during workshops and to feed staff. Lunch is covered,

but dinner is not.

|

Expense

|

Monthly

|

Annual Cost

|

|

Rent

|

800.00

|

9,600.00

|

|

Utilities

|

60.00

|

720.00

|

|

Food

|

300.00

|

3,600.00

|

|

Meeting

Fees

|

83.00

|

996.00

|

|

Insurance

Coverage

|

83.00

|

996.00

|

|

Travel

|

83.00

|

996.00

|

|

Structure

& Payment Consult

|

84.00

|

1,008.00

|

|

Training

Class

|

2,000.00

|

24,000.00

|

|

3,493.00

|

41,916.00

|

Table 5:

Organizational Expenses

Thank to donations provided by our

participating providers as well as our individual community members we have

already been provided a significant amount of our office supplies.

Supplementing the office supplies are the food and drinks provided courtesy of

our local convenience stores. These in kind donations provide a savings cost

of $17,960.

|

Type

of Donation

|

Quantity

|

Cost Per

|

Total

|

|

Laptop

Computers

|

10

|

$1,500.00

|

$15,000.00

|

|

Toner

Ink (Boxes)

|

10

|

$100.00

|

$1,000.00

|

|

Printer

All in One

|

1

|

$300.00

|

$300.00

|

|

Writing

Utensils

|

30

|

$10.00

|

$300.00

|

|

Clips,

Staples, Holders

|

30

|

$7.00

|

$210.00

|

|

Filing

cabinet

|

4

|

$50.00

|

$200.00

|

|

Paper

(5000sheets)

|

3

|

$60.00

|

$180.00

|

|

Tables

(Portable)

|

5

|

$40.00

|

$200.00

|

|

Chairs

(Portable)

|

20

|

$15.00

|

$300.00

|

|

Food

(Canned Goods)

|

40

|

$3.00

|

$120.00

|

|

Drinks

(24-Packs)

|

5

|

$30.00

|

$150.00

|

|

2,115.00

|

17,960.00

|

Table 6: In kind Donations

3.2 Model Sustainability

The program hopes to achieve

savings by increasing the flexibility of primary care practices through

alternative payment models. The better alternatives allow greater access to

health care. Running parallel to the new payment models are the improved EHR utilization

efforts. Increased efficiency of the health records will allow allied health

staff to better aid the physician. Having the numbers and the documents on

file will also allow consultants and third party services, when permitted, to compile

reports. The table below illustrates the best possible savings that can be

achieved with better training of electronic health records.

|

Type

of Benefit

|

Quantity

|

Money Opp Cost

|

Number of Patients

|

Gross

Savings

|

|

Cost

Performance

|

30

|

$170.00

|

1,500.00

|

$7,650,000.00

|

|

Physician

Coordination

|

30

|

$10.00

|

1,500.00

|

$450,000.00

|

|

Preventative

Health

|

30

|

$50.00

|

1,500.00

|

$2,250,000.00

|

|

$10,350,000.00

|

Table 3: Possible Health Savings

Evaluation

Evaluation of the entire operation

will be broken into chunks of audits and meetings. Each quarter will be

evaluated through its action process. Since the earlier months are spent

setting up the suggestions and systems, focus will be on the reports produced

by the project managers. These reports will be cross-examined with patient

data and health professional accounts of their clinical operations through a

one-on-one discussion with the health professionals. Of the first three

quartiles all the reports must be accurate to set a strong foundation for

later suggestions. The information must be at least 90% accurate to verify for

a solid foundation. The accuracy will be determined by cross checking with

medical professionals from the private practice. If the first three quartiles

do not reach the threshold of 90%, another round of reports will be required

by the next quartile. This second time more emphasis will be placed on that

specific clinic.

Later quarterlies will focus more

on workshop and suggestion implementation. A survey of the workshops will

provide QMPA staff with overall morale of the healthcare professionals from

each practice. It is expected that some of the practices will have health

professionals with little to no motivation to change policies or workflows.

Hope is to have the possible benefits of new EHR procedures dangled in front

of the health professionals to act an incentive to already existing problems.

Suggestions that are implemented should be evaluated on a before versus after

basis. If at least 50% of the suggestions are successfully implemented, then

the later quarterlies can be considered effective.

To evaluate final long-term

outcomes, we will examine the change in the data connected to the nine core

assessments. Changes regarding practice workflow comparison will be made from

past program manager reports to current conditions. If there is a marked

improvement on at least 50% of suggestions, the program will be considered a

success. In addition, the patients will receive a survey at the end of their office

visit to verify if they identified new payment models as responsible for their

visit.

Supporting Documents

Appendix 1 – Placement of the CARE Program within

QMPA

Appendix 2 – CARE Program

Appendix 3 – Overall Total Project Budget for

Electronic Healthcare Initiative

|

RFP, Project Budget (Required)

|

|||

|

Robert

Wood Johnson Foundation

|

Queens

Medical Professional Association

|

||

|

Expenses

|

Total Project Expenses

|

Amount Requested from Funder

|

|

|

Salary and Benefits

|

$375,204.00

|

$375,204.00

|

|

|

Contract Services (consulting, professional, fundraising)

|

$1,008.00

|

$1,008.00

|

|

|

Occupancy (rent, utilities, maintenance)

|

$10,320.00

|

$10,320.00

|

|

|

Training & Professional Development

|

$24,000.00

|

$24,000

|

|

|

Insurance

|

$996.00

|

$-

|

|

|

Travel

|

$996.00

|

$-

|

|

|

Supplies

|

$17,960.00

|

$-

|

|

|

Evaluation

|

$5,000.00

|

$5,000

|

|

|

Conferences, meetings, etc.

|

$996.00

|

$996

|

|

|

TOTAL EXPENSES

|

$536,840

|

$416,528

|

|

|

Revenues

|

Committed

|

Pending

|

|

|

Contributions, Gifts, Grants, & Earned Revenue

|

|

|

|

|

Local Government

|

$-

|

$50,000

|

|

|

State Government

|

$100,000

|

$-

|

|

|

Federal Government

|

$-

|

$-

|

|

|

Individuals

|

$5,000

|

$-

|

|

|

*Corporation-Jones Surgical Instruments

|

$1,000

|

$-

|

|

|

Membership Income

|

$3,000

|

$1,500

|

|

|

Fundraising Events (net)

|

$500

|

$-

|

|

|

Investment Income

|

$10,000

|

$-

|

|

|

In-Kind Support

|

$17,690

|

$-

|

|

|

TOTAL REVENUES

|

$137,190.00

|

$51,500.00

|

|

References

Bakris, G., & Sorrentino, M. (2018). Redefining

hypertension — assessing the new blood-pressure guidelines. N Engl J

Med, 378(6), 497-499. 10.1056/NEJMp1716193 Retrieved from https://doi-org.ez-proxy.brooklyn.cuny.edu/10.1056/NEJMp1716193

Center for Workforce Studies, Erikson, C., Jones, K.,

& Whatley, M. (2015). 2015 state physician workforce data book.().Association

of American Medical Colleges. Retrieved from https://members.aamc.org/eweb/upload/2015StateDataBook%20(revised).pdf

Clough, J. D., Richman, B. D., & Glickman, S. W.

(2015). Outlook for alternative payment models in fee-for-service medicare. Jama, 314(4),

341-342. 10.1001/jama.2015.8047

Fleurant, M., Kell, R., Jenter, C., Volk, L. A.,

Zhang, F., Bates, D. W., & Simon, S. R. (2012). Factors associated

with difficult electronic health record implementation in office practice10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000689

Friedberg, M. W., Chen, P. G., White, C., Jung, O.,

Raaen, L., Hirshman, S., . . . Lipinski, L. (2015). Effects of health care

payment models on physician practice in the united states. Rand Health

Quarterly, 5(1), 8.

Friedman, D. J., Parrish, R. G., & Ross, D. A.

(2013). Electronic health records and US public health: Current realities and

future promise. American Journal of Public Health, 103(9),

1560. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301220

Helmchen, L. A. (2009). Fee-for-service. In R. M.

Mullner (Ed.), Encyclopedia of health services research (pp.

399-401). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. Retrieved from http://link.galegroup.com.ez-proxy.brooklyn.cuny.edu:2048/apps/doc/CX3208000153/GVRL?u=cuny_broo39667&sid=GVRL&xid=2d45edc8

Hydari, M., Telang, R., & Marella, W. (2015).

Electronic health records and patient safety. Communications of the

ACM, 58(11), 30-32. 10.1145/2822515

Jha, A. K., DesRoches, C. M., Campbell, E. G.,

Donelan, K., Rao, S. R., Ferris, T. G., . . . Blumenthal, D. (2009). Use of electronic

health records in U.S. hospitals. N Engl J Med, 360(16),

1628-1638. 10.1056/NEJMsa0900592 Retrieved from https://doi-org.ez-proxy.brooklyn.cuny.edu/10.1056/NEJMsa0900592

King, L., Hinterland, K., Dragan, L., Driver, C. R.,

Harris, T. G., Gwynn, R. C., . . . Bassett, M. T. (2015). Community

health profiles 2015, queens community district 4: Elmhurst and corona. ().New

York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

Laberge, M. (2013). Hyperlipidemia. In K. Key

(Ed.), The gale encyclopedia of diets: A guide to health and nutrition(2nd

ed. ed., pp. 613-617). Detroit: Gale. Retrieved from http://link.galegroup.com.ez-proxy.brooklyn.cuny.edu:2048/apps/doc/CX2760100169/GVRL?u=cuny_broo39667&sid=GVRL&xid=39d2a214

Larsen, K. N., Kristensen, S. R., & S�gaard, R. (2018).

Autonomy to health care professionals as a vehicle for value-based health care?

results of a quasi-experiment in hospital governance. Social Science

& Medicine; Social Science & Medicine, 196, 37-46.

10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.11.009

McPherson, D. (2008). Body mass index (BMI). In S.

Boslaugh (Ed.), Encyclopedia of epidemiology (pp. 101-103).

Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. Retrieved from http://link.galegroup.com.ez-proxy.brooklyn.cuny.edu:2048/apps/doc/CX2660800057/GVRL?u=cuny_broo39667&sid=GVRL&xid=837b8149

Nussbaum, S., Mcclellan, M., & Metlay, G. (2018).

Principles for a framework for alternative payment models. Jama, 319(7),

653. 10.1001/jama.2017.20226

Office of the Professions. (2018). License statistics.

Retrieved from http://www.op.nysed.gov/prof/med/medcounts.htm

Porter, M. E. (2012). In Guth C. (Ed.), Redefining

german health care moving to a value-based system. Heidelberg; Heidelberg,

Germany ; New York: Heidelberg : Springer.

Preskitt, J. T. (2008). Health care reimbursement:

Clemens to Clinton. Proceedings (Baylor University.Medical

Center), 21(1), 40-44. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2190551/

Rosenbaum, L. (2015). Transitional chaos or enduring

harm? the EHR and the disruption of medicine. N Engl J Med, 373(17),

1585-1588. 10.1056/NEJMp1509961 Retrieved from https://doi-org.ez-proxy.brooklyn.cuny.edu/10.1056/NEJMp1509961

Schimpff, S. (2014). How many patients should A

primary care physician care for? Retrieved from https://medcitynews.com/2014/02/many-patients-primary-care-physician-care/?rf=1

The Robert Graham Center. (2015). Primary care

physician mapper. Retrieved from https://www.graham-center.org/rgc/maps-data-tools/interactive/primary-care-physician.html

United States Government, Accountability Office.

(2014). Electronic health record programs : Participation has

increased, but action needed to achieve goals, including improved quality of

care : Report to congressional committees Washington, District of

Columbia : United States Government Accountability Office.

US Census Bureau. (2016). Quick facts, queens county

(queens borough), new york; united states. Retrieved

from https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/queenscountyqueensboroughnewyork,US/PST045216

[1]

Accounting for physicians of general internal medicine, family medicine,

general practice, and pediatrics using data from 2013.

[2]

Recommended patient loads for quality care are 800 patients or less (Schimpff,

2014)

[3]

Assuming patients present at least one symptom and do not suffer from

comorbidity.

[4]

The exception being core assessment number 10, which tests for effective

communication of patient data rather than focusing on patient health.

[5]

Refer to Appendix 1 under the supporting documents.

[6]

Refer to Appendix 2 under the supporting documents.